If social media is an expression of public sentiment, then it seems significant that perhaps the most widely shared tweet on Friday's terror attacks in Paris was not about Paris at all but rather was about another terror attack, earlier that week, in Beirut:

The photo in this tweet is not, in fact, from last week's blast in Beirut. Rather, it is from 2006, during Israel's war against Hezbollah in Lebanon. But what is most striking to me about this tweet, now shared by well over 50,000 people, is that it's wrong: The media has, in fact, covered the Beirut bombings extensively.

The New York Times covered it. The Washington Post, in addition to running an Associated Press story on it, sent reporter Hugh Naylor to cover the blasts and then write a lengthy piece on their aftermath. The Economist had a thoughtful piecereflecting on the attack's significance. CNN, which rightly or wrongly has a reputation for least-common-denominator news judgment, aired one segment after another on the Beirut bombings. Even the Daily Mail, a British tabloid most known for its gossipy royals coverage, was on the story. And on and on.

Yet these are stories that, like so many stories of previous bombings and mass acts of violence outside of the West, readers have largely ignored.

It is difficult watching this, as a journalist, not to see the irony in people scolding the media for not covering Beirut by sharing a tweet with so many factual inaccuracies — people would know that photo was wrong if only they'd read some of the media coverage they are angrily insisting doesn't exist.

"Nobody is going to read this"

Watching this debate unfold, my mind goes back to one of the first bombings I covered, in early 2010.

That April, a series of bombs ripped through Baghdad, killing 85 people. The city has not known what we might call total peace for some years, but it was a period of relative calm. The bombings, in addition to being a humanitarian disaster, also came at a tense political moment.

It was a big, scary, and important event. Writing from the US, at that point as an editor at the Atlantic, I tried as best I could to capture what made it so important. I was traveling that day, and I remember calling the web editor to discuss some revisions and urge him to position it at the top of the homepage. He readily agreed. But when I began discussing the headline and the photo with him, and I asked what he thought would best help get readers interested in the story, he laughed.

"It doesn't matter what art we put with this or if it's at the top of the homepage," he said. "Nobody is going to read this."

He was right. No matter how much we promoted the story, no matter how many times and ways we put it in front of readers, they were not interested.

I refused to believe that the editor had been right, and instead I blamed myself — my story must have been boring or poorly headlined, or the lede was too dry. Or maybe it was just that this was Baghdad, and readers had in the preceding months not come to appreciate the city's brief calm — another way I might have failed them.

I still hold out hope that it's possible to get readers interested. And I have been trying over and over in the five years since to get readers engaged with these stories. Incidents of mass violence in the world are, I believe, desperately important for readers to know. Not just so that readers can offer sympathy to the victims, but so that they may better understand what's happening in the world and thus can better and more actively participate in whatever role they have to play as voters and global citizens. But unless the victims are either children or Christian, I have never really succeeded in getting readers to care about such bombings that happen outside of the Western world.

Most recently, we tried it with the June bombing in Kuwait and the August bombing in Bangkok. We covered the series of violent attacks this summer in Turkey. On Beirut alone, I wrote about the October 2012 bombing and the December 2013 bombing, and, yes, my colleagues wrote about last week's bombing there.

It's not just me, of course: My peers throughout the media have dutifully and diligently covered such attacks for years. Local reporters and foreign correspondents out in the field have of course done far more than I have, spending days interviewing victims and painstakingly reconstructing events — despite knowing that readers were all but certain to ignore the stories. "Nobody is going to read this" is a phrase we've grown accustomed to hearing.

The gap between true narratives and true facts

I was thus a bit surprised, over the past week, to see an outpouring of reader outrage. So what's driving people to scold media outlets for not covering an event they have in fact covered extensively?

At the most basic level, I suspect this may reflect a very human tendency with which we in the media are all too familiar: People start with a narrative they feel is true, and then look for evidence to support that narrative.

In this case, people began with the narrative that the world gives lesser weight to the suffering of non-Westerners — absolutely true — and then latched onto a piece of evidence, the supposed lack of media coverage, that supported their narrative. The fact that the media has in fact covered Beirut, and that the tweet capturing this outrage contained a photo from 2006, was in many ways beside the point.

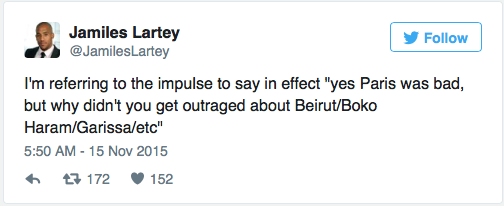

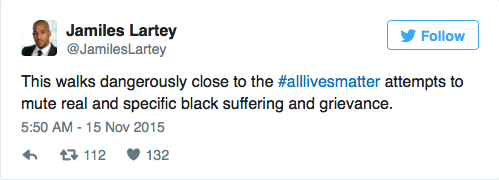

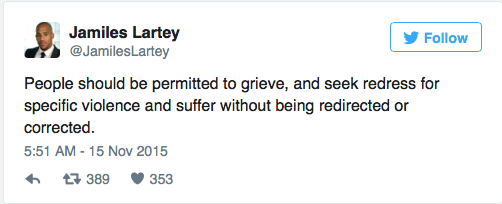

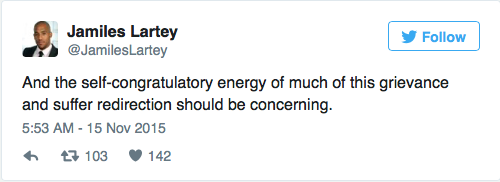

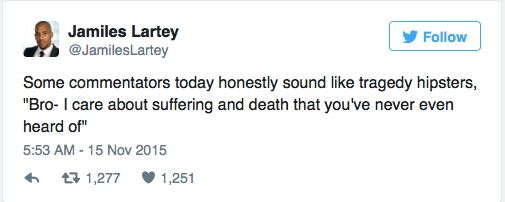

But facts do matter, and emphasizing wrong facts can lead us astray — not only because they lead us to blame the wrong villain. Jamiles Lartey, in an insightful series of tweets reflecting on all this, notices some concerning trends in a lot of this discourse that might otherwise be well-intentioned:

The New York Times covered it. The Washington Post, in addition to running an Associated Press story on it, sent reporter Hugh Naylor to cover the blasts and then write a lengthy piece on their aftermath. The Economist had a thoughtful piecereflecting on the attack's significance. CNN, which rightly or wrongly has a reputation for least-common-denominator news judgment, aired one segment after another on the Beirut bombings. Even the Daily Mail, a British tabloid most known for its gossipy royals coverage, was on the story. And on and on.

Yet these are stories that, like so many stories of previous bombings and mass acts of violence outside of the West, readers have largely ignored.

It is difficult watching this, as a journalist, not to see the irony in people scolding the media for not covering Beirut by sharing a tweet with so many factual inaccuracies — people would know that photo was wrong if only they'd read some of the media coverage they are angrily insisting doesn't exist.

"Nobody is going to read this"

Watching this debate unfold, my mind goes back to one of the first bombings I covered, in early 2010.

That April, a series of bombs ripped through Baghdad, killing 85 people. The city has not known what we might call total peace for some years, but it was a period of relative calm. The bombings, in addition to being a humanitarian disaster, also came at a tense political moment.

It was a big, scary, and important event. Writing from the US, at that point as an editor at the Atlantic, I tried as best I could to capture what made it so important. I was traveling that day, and I remember calling the web editor to discuss some revisions and urge him to position it at the top of the homepage. He readily agreed. But when I began discussing the headline and the photo with him, and I asked what he thought would best help get readers interested in the story, he laughed.

"It doesn't matter what art we put with this or if it's at the top of the homepage," he said. "Nobody is going to read this."

He was right. No matter how much we promoted the story, no matter how many times and ways we put it in front of readers, they were not interested.

I refused to believe that the editor had been right, and instead I blamed myself — my story must have been boring or poorly headlined, or the lede was too dry. Or maybe it was just that this was Baghdad, and readers had in the preceding months not come to appreciate the city's brief calm — another way I might have failed them.

I still hold out hope that it's possible to get readers interested. And I have been trying over and over in the five years since to get readers engaged with these stories. Incidents of mass violence in the world are, I believe, desperately important for readers to know. Not just so that readers can offer sympathy to the victims, but so that they may better understand what's happening in the world and thus can better and more actively participate in whatever role they have to play as voters and global citizens. But unless the victims are either children or Christian, I have never really succeeded in getting readers to care about such bombings that happen outside of the Western world.

Most recently, we tried it with the June bombing in Kuwait and the August bombing in Bangkok. We covered the series of violent attacks this summer in Turkey. On Beirut alone, I wrote about the October 2012 bombing and the December 2013 bombing, and, yes, my colleagues wrote about last week's bombing there.

It's not just me, of course: My peers throughout the media have dutifully and diligently covered such attacks for years. Local reporters and foreign correspondents out in the field have of course done far more than I have, spending days interviewing victims and painstakingly reconstructing events — despite knowing that readers were all but certain to ignore the stories. "Nobody is going to read this" is a phrase we've grown accustomed to hearing.

The gap between true narratives and true facts

I was thus a bit surprised, over the past week, to see an outpouring of reader outrage. So what's driving people to scold media outlets for not covering an event they have in fact covered extensively?

At the most basic level, I suspect this may reflect a very human tendency with which we in the media are all too familiar: People start with a narrative they feel is true, and then look for evidence to support that narrative.

In this case, people began with the narrative that the world gives lesser weight to the suffering of non-Westerners — absolutely true — and then latched onto a piece of evidence, the supposed lack of media coverage, that supported their narrative. The fact that the media has in fact covered Beirut, and that the tweet capturing this outrage contained a photo from 2006, was in many ways beside the point.

But facts do matter, and emphasizing wrong facts can lead us astray — not only because they lead us to blame the wrong villain. Jamiles Lartey, in an insightful series of tweets reflecting on all this, notices some concerning trends in a lot of this discourse that might otherwise be well-intentioned:

But I am still sympathetic to the anger. The underlying point behind this criticism is not really about the media, after all. Rather, it's about a sense that the world at large has ignored Beirut's trauma and that it ignores similar traumas throughout the world if they occur in the wrong places; that it does not offer the same sympathy to victims outside of wealthy or Western countries

This is entirely correct. People in Beirut do feel forgotten; they do feel that the world has given Paris more sympathy and more attention than it has to them. We know this in part because the New York Times, as part of its running coverage of the Beirut blasts, published an article reporting on these feelings of neglect in Beirut

There's more than just a supposed lack of media coverage at stake here, and the world's attention manifests itself in ways beyond just the frequency or attendance of sympathy rallies. The Syrian refugee crisis, for example, is something that has hit both France and Lebanon. Yet the world's response — not just its words but its actions — has given significantly more weight to France's refugee burden than to Lebanon's.

France has received 6,700 Syrian asylum claims, and expects to receive several thousand more. In response, European and other Western leaders have convened repeated international summits to try to help France and other Western countries figure out how to deal with this. By comparison, Lebanon currently hosts 1.1 million Syrian refugees — equivalent to one-quarter of the country's population. In response, the world has given some aid but has fallen far short of the United Nations' annual funding requests. Lebanon is enduring not just a tremendous economic burden but a political burden. The world truly does care more about France, in this respect and in many others, than about Lebanon. And that has consequences.

It would be easy to blame the media for this, to say that if only media outlets covered Beirut rather than ignoring it, the world might pay attention. I have bad news: The media does cover Beirut, just as it has been covering Lebanon's refugee plight for years. That's an uncomfortable truth, because rather than giving us an easy villain, it forces us to ask what our own role might be in the world's disproportionate care and concern for one country over another.

But if that reflection leads people to express greater interest in what happens in Beirut or Abuja or Baghdad, then few will be happier than those of us in the media. We've been trying for years to break through reader apathy and disinterest. If we take some unfair criticisms but it gets people to finally pay attention, I think that is a trade-off every reporter on Earth would accept.

This is entirely correct. People in Beirut do feel forgotten; they do feel that the world has given Paris more sympathy and more attention than it has to them. We know this in part because the New York Times, as part of its running coverage of the Beirut blasts, published an article reporting on these feelings of neglect in Beirut

There's more than just a supposed lack of media coverage at stake here, and the world's attention manifests itself in ways beyond just the frequency or attendance of sympathy rallies. The Syrian refugee crisis, for example, is something that has hit both France and Lebanon. Yet the world's response — not just its words but its actions — has given significantly more weight to France's refugee burden than to Lebanon's.

France has received 6,700 Syrian asylum claims, and expects to receive several thousand more. In response, European and other Western leaders have convened repeated international summits to try to help France and other Western countries figure out how to deal with this. By comparison, Lebanon currently hosts 1.1 million Syrian refugees — equivalent to one-quarter of the country's population. In response, the world has given some aid but has fallen far short of the United Nations' annual funding requests. Lebanon is enduring not just a tremendous economic burden but a political burden. The world truly does care more about France, in this respect and in many others, than about Lebanon. And that has consequences.

It would be easy to blame the media for this, to say that if only media outlets covered Beirut rather than ignoring it, the world might pay attention. I have bad news: The media does cover Beirut, just as it has been covering Lebanon's refugee plight for years. That's an uncomfortable truth, because rather than giving us an easy villain, it forces us to ask what our own role might be in the world's disproportionate care and concern for one country over another.

But if that reflection leads people to express greater interest in what happens in Beirut or Abuja or Baghdad, then few will be happier than those of us in the media. We've been trying for years to break through reader apathy and disinterest. If we take some unfair criticisms but it gets people to finally pay attention, I think that is a trade-off every reporter on Earth would accept.

RSS 訂閱

RSS 訂閱