|

"I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated."

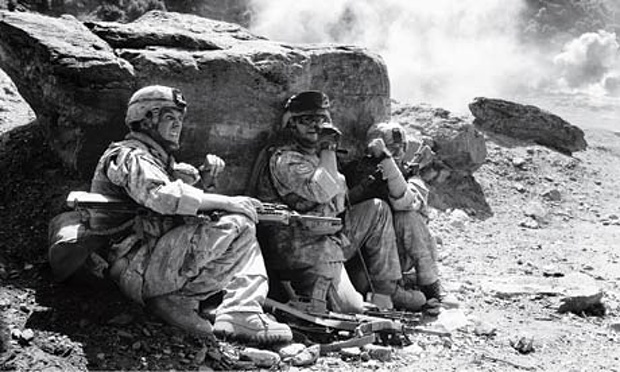

-James Nachtwey- 小學時期正值伊拉克攻打科威特,當時美國以世界警察的形像介入,當時其實跟本不知道戰爭為何物。只知道「愛國者導彈」對「飛毛腿導彈」、美軍的「沙漠風暴」很有型,以為美軍維持世界秩序,伊拉克侯賽因是壞蛋。對於戰爭的認識只是新聞裡的一些名詞,電影、遊戲之中的印像。嚴格來說,我們這一代香港人不知真正的戰爭為何物,戰爭跟我們沾不上邊。 人大了,發現很多事情不是這樣簡單。戰爭其實離我們很近,全球一體化的趨勢下更是如此,一切都環環緊扣,息息相關。以往發生於偏遠國度的戰爭,已經以西方大城市為舞台在上演,紐約911,巴黎恐襲,日本記者後籐健二被斬首。追問箇中因由,千絲萬縷,誰是誰非根本無從說起。 除了尋根究底,我們能夠看見戰爭中的每一個「人」嗎?還是戰爭中的「人」只是被消耗的「物品」、「數字」?殺戮、悲傷、不幸真的無可避免?歷史、文化、地理是真正原因?人擁有選擇嗎?能夠奪回自主,不再受有形無形的擺佈?能夠創造更好的世界? 人類能否在彼此消耗胎盡前走出這個輪迴? 黃宇恒 二零一五年十二月十九日 二零一五年十二月二十七日

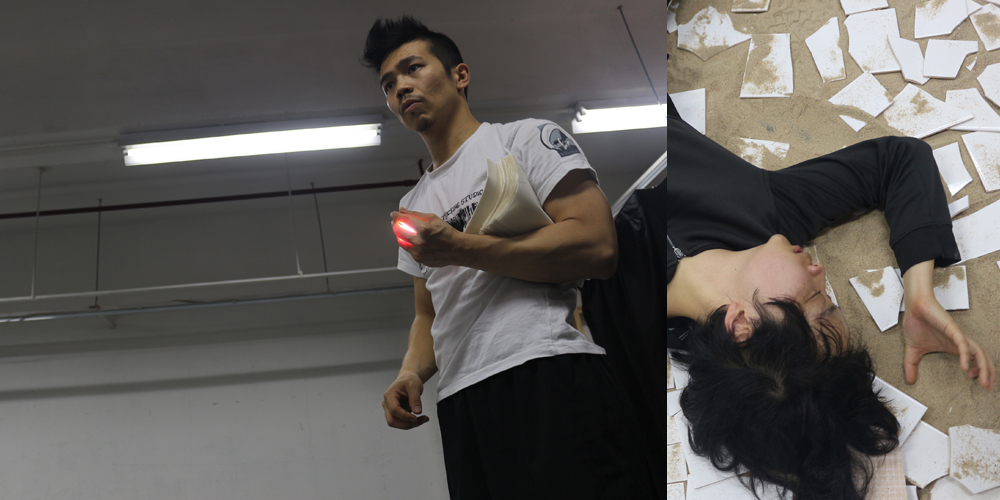

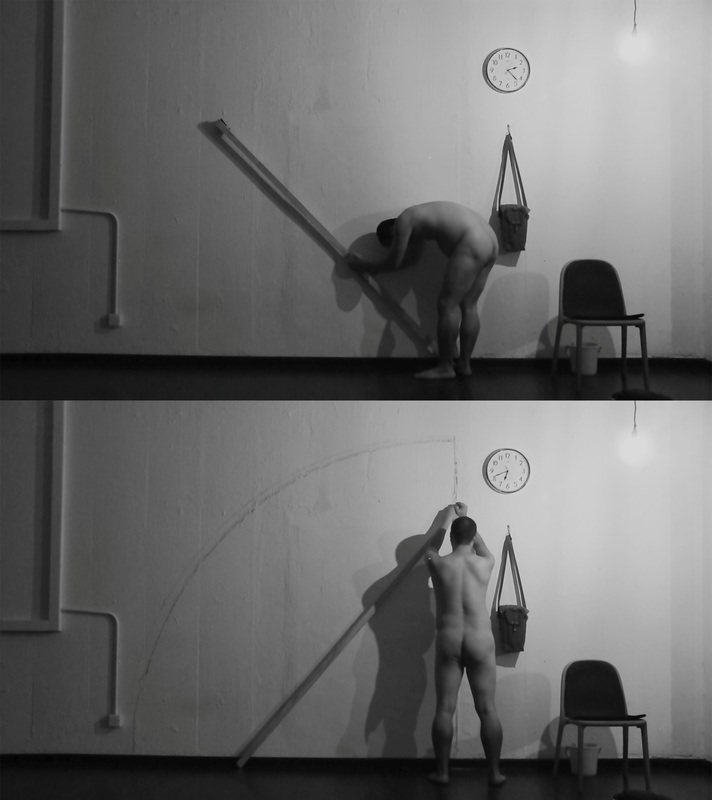

何來 何應豐常和我分享與對話,留學倫敦時其中一次對話,正值創作了第一個二十四小時的"行為錄像"<一念。二十四分>(行為錄像一詞,未知是不是最合適的名詞界定我的作品,但我把行為+錄像雙拼起來,既不想它是現場行為,也不想它成為太多設定及技術的錄像,卻有點像不是這又不是那的狀況,像燒味雙拼飯,像飲品鴛鴦。)我說整合了自己創作的理念,還是關於一些作為人很根本的存在問題,或許,起碼作為扣問自己一些存在存有的問題。時間,身體,意念。三者與生俱來,組成了現世存在的我,時間是無盡地向前累積,身體是時間線上的一點或一條很短的線,意念卻暫存在身體這媒介之中,卻不知何來,也不知何去,卻可一念之間,思故,虛幻,改變下一刻的我。 拆字 向何應豐分享了我的創作理念,他就回了一些拆字來啟導我一些思考方向。「時,日之寺也!間,是日給門卡住了的"有限空間"!念,今之心?其"頭"之源,何種?又是另一豆之緣起和"頁"數!過去,現在將來,從來互相扣住,沒完沒了。」當中"念"一字,正正包含了我探討的三個元素,今之心,今,當下一刻,心,物理上,身體之一部份,合之為念,「念」既然包括了時間,我嘗試把作品叫作<一念。二十四分>,賦予一個念的時限,而這個時限,是你是我也一同都要經歷經驗的,即一天的二十四小時,不能多,不能少,除非是生命的開始及終止,否則生命中有可多可少次的二十四小時。而這個時限,七除八扣,一天可產生多少個自己的意念,而每一個念,又可以遊走多遠多久?時,間,如何應豐所說,一日之寺,被門卡住了的空間,有限之時,有限之空間,在這囚牢之內,我們流失多少在他人他事他物之上?又有多少「時」、「間」可給自己栽種及閱覽一己之「豆」?我,只是坐下來,凝望一頁揭另一頁這些微動作。 囚 二十四小時,既有之時限,我視作是一種框架,也可以是囚牢。把它視作有時限存在的空間,佈置這奇異囚室,成為我身體唯一的勞作。囚禁於內,每時每刻成了我要體驗或體味的細緻經歷。在當時今世,要切斷一天與外界的聯絡,已被視為是一種無理無法的行為。於我而言,進入及離開這二十四小時的囚牢,也產生了無形的壓迫感。因為進入,身體對溫度、空間、或空間以外的人或事感到焦慮。因為進入,時間的觀念也在無限地拉長了,心在盤算著時鐘上的12時刻,哪些時刻較易渡過,哪些時刻是一個大關口,配合窗外的天黑與天亮,時間成為一套你不可提早離場的電影,你必須閱歷完成。因為進入,要完成一件事,產生一個意念,卻在一念之下,產生更多的念。念自身,念故人,念當刻,念吃,念睡,念盛年。以"一念"在二十四小時內推行一個行動,"念"卻傾瀉在囚牢內一地。 離。迷離 目前共創作了三件<一念。二十四分>的作品,經驗了四次的二十四小時慢行動作。(其中一次因在創作過程中的道具意外,也迫令自己完成下去。)因慾念傾瀉,慾念包括"為完成作品"之慾,求衣服蔽體之慾,求吃之慾,每次離開囚牢時之狀況不一,也可視為一種修正修行。在第一個創作<一念。二十四分:照>時,因環境的迫使,及低氣溫下,加上是第一次的"挑戰"(這是何其明顯的"為了完成作品"之慾),在最後一小時,當我穿回衣服時,在衣領口望出地上由自己身體壓印的墨汁軌跡,我看到的是一片頹垣敗瓦。是幻像?我再三確認自己視力是否正常,或是否身體的虛弱出現幻覺。又不是,感覺像看立體照片,只要把自己視線對焦,立體的影像就出現了。這令我直接聯想到"井"下的是什麼世界?(井,是我最初從村上春樹的小說抽取的一個物像作為開始創作的路向)。而且,在地上畫的井,正正是想把現場的人及媒介都吸進去,我把這廢墟幻像視作這次作品或行動吐納出來的"另一作品",不能紀錄,不能呈現,它只出現在"我"眼前,刻在"我"創作記憶內。 第二個作品<一念。二十四分:書>,也是在倫敦完成,時值畢業展籌備,要在此前完成作品,汲取了第一次的刻苦經驗,我回歸練習時的近鏡拍攝半身像,使得可走動的空間更小。因為太著意第一次的不足之處,在預備離去的一小時,只記著如何刻意加慢動作,使得身體成了接收指令的機械,意念就只是如何把作品操控在高完成度的假大空。使得作品只得在「時間」這一元素上,體現出了質感。 一卷嘔吐而成的水墨,也好比自己的人生,跟從指令去達成他者的期望。 回港後,再會何應豐,借出流白之間,給我駐留創作,正好這系列創作,有未完整的感覺,何不留駐發現另一個二十四小時?回港,感覺脫離了另一個囚禁的地方移往另一個囚禁之地。一切節奏加速,自己身體調整不到,變得追趕他人的步伐,面對何應豐如是。回港後,自己在不同範疇,不同人事上,不斷走馬燈式的接觸。還記得第一次計劃在流白之間做<一念。二十四分:推>之前,何應豐介紹一音樂朋友認識,何不嘗試一起交流現場創作二十四小時?我接觸了對方,當然,突如其來的二十四小時創作,不易可安排。心理上及生理上,自己感覺左撲右撲,何其的勞累。流白現場一切裝設好,正要進入二十四小時,突然感緊張而致內急,處理好後,唯有把時鐘調回一小時前,等待另一個偽半夜十二時。躺在地上等待,身體自然關上一切能源,睡了起來。那時,我才明白,努力與勞力,也得好好分別清楚,也明白,完成二十四小時,不應視為藝能般的創舉,而是囚禁之下,正好是為了閱讀自身當下的狀況。這次所謂的「衝關」失敗,帶來了創作啟示。與何應豐分享了失敗經驗,我反而放下心頭石。(雖則我在開始前曾告訴他身體太累了,有很大壓力,他仍對我說累了的身體有累了的狀況呈現,笑了,其實是累得自己在創作大門前跪了下來。) 一星期後,再次預備,何氏再發來短訊:「如來如去。」心境從未如此平靜自然,"如來"進入二十四小時,"如去"完成。沒有心跳急促地想逃離此空間,沒有告誡自己哪一部份動作快了,甚至乎不在意時間的流動快慢,天光天黑,一切來得理所當然,只在二十四小時內重覆地搬動木棒。這次經驗,比較貼近薜西弗的狀況,接受身體當時的狀態,時間的流逝,單一意念的提昇(少了很多雜念)。如來如去,一呼一吸。是我希望在此系列探求一的一種狀態。而這次我不敢說達到了,而是說我接近了。 下一回 去到第三個作品,才慢慢釐清每個作品在訴說什麼?<照>,是扣問自己創作的媒介,行為藝術與攝影的相互關係,自己如何閱讀二者當下的存在狀況,或許,我只是閱讀一個行為藝術創作者及一個攝影者的存在狀況。把二人都投進時間的攪拌器中,希望各自在創作質感上起些變化吧。<書>,是走進一人的囚禁空間裡,沒有他者存在下,默默書寫自己的情書,赤裸裸地呈現生命的血淚,慶幸,偶然有陽光照進囚室裡。<推>卻正正寫照當下自己的創作狀態,每天重覆著推動創作,看似徙労無功,卻每每細閱每天曾推動過的路上痕跡,終有一天,接受了命運如是,擁抱重擔。下一回,下一回,抽走更多元素,還剩下什麼,閱讀得更多嗎?

Adam Ferguson, Afghanistan, 2009 I was one of the first on the scene. The Afghan security forces normally shut down a suicide bombing like this pretty quickly. I was able to get to the epicentre of the explosion. It was carnage, there were bodies, flames were coming out of the buildings. I remember feeling very scared because there was still popping and hissing and small explosions, and the building was collapsing. It was still very fresh and there was a risk of another bomb. It was one of those situations where you have to put fear aside and focus on the job at hand: to watch the situation and document it. This woman was escorted out of the building and round this devastated street corner. It epitomised the whole mood – this older woman caught in the middle of this ridiculous, tragic event. I wish I could have found out how her life unravelled, but as soon as the scene was locked down, I ran back to the office to file. As a photographer, you feel helpless. Around you are medics, security personnel, people doing good work. It can be agonisingly painful to think that all you're doing is taking pictures. When I won a World Press award for this photograph, I felt sad. People were congratulating me and there was a celebration over this intense tragedy that I had captured. I reconciled it by deciding that more people see a story when a photographer's work is decorated. Alvaro Ybarra Zavala, Congo, November 2008 The situation was very tense – people were drunk and aggressive. I was with two other photographers most of the time, but at this moment I went back to the road alone. I saw three soldiers smoking, playing with their guns, and felt safe – I don't know why. Then I saw a man with a knife in his mouth, coming out of the bush – he was holding up a hand like a trophy. The soldiers started laughing and firing in the air. I didn't think about it and began shooting. He walked directly at me. People surrounded us, celebrating. I thought, "Don't do anything crazy, just act like you're part of this crazy party." When I got to the hotel, I showed the other photographers. They said, "Do you realise you could have been killed?" Only then did it hit me how dangerous it had been. Years after I took this picture, every time I see it I feel scared again. I really hate this shot. It's the worst face of humankind. I always ask myself, "Why do I do this job?' And the answer is: I want to show the best and worst face of humankind. Every time you go to a conflict, you see the worst. We need to see what we do to be able to show future generations the mistakes we make. The guy with the knife in his mouth is a human being like the rest of us. What's important is that we show what human beings are capable of. The day I don't do that with my photography is the day I'll give up and open a restaurant. Lynsey Addario, Libya, March 2011 I had been in Libya for just over two weeks, shooting the insurgency. Pictures like this, of inexperienced rebels being fired on by machine guns and mortars. On 15 March, myself and three other journalists were captured by Gaddafi's troops. They made us lie in the dirt, put guns to us. We were pleading for our lives. They started groping me very aggressively, touching my breasts and butt. Then we were tied up, blindfolded and moved from place to place for six days. The first three days were very violent – I was punched in the face several times, groped nonstop. At that point, it was hard to justify why I put myself in that situation. When our captors left us alone, we spoke about what we'd do if we got out. I said I'd probably have to get pregnant because I've put my husband through a lot – I was kidnapped in Fallujah in 2004, and I was in a car that flipped just months before our wedding. Some of us contemplated whether we wanted to continue covering conflicts; whether it was worth the hardships we put our families through. When we got out, I felt surprisingly OK. We'd survived – when you survive, this job is always worth the risk. Then a few weeks later Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros were killed in Misrata, which sent me into a tailspin. This job takes a lot of skill, but a lot of it is luck. When friends die, you wonder if it's worth the price. João Silva, Afghanistan, October 2010 I'd been in Afghanistan for a month when I stepped on the landmine. I was the third man in line, and as I put my foot down, I heard a metallic click and I was thrown in the air. I knew exactly what had happened. As the soldiers dragged me away from the kill zone, I took these pictures. When people around me have been hurt or killed, I've recorded it. I had to keep working. The soldiers were yelling for the medics. I knew my legs had gone, so I called my wife on the satellite phone and told her not to worry. The pain came later, back in intensive care, when infections set in and they nearly lost me a couple of times. I've spent enough time out there for my number to come up. I was one of the few who kept going back to Iraq. People think you do this to chase adrenaline. The reality is hard work and a lot of time alone. Firefights can be exciting, I'm not going to lie, but photographing the aftermath of a bomb, when there's a dead child and the mother wailing over the corpse, isn't fun. I'm intruding on the most intimate moments, but I force myself to do it because the world has to see those images. Politicians need to know what it looks like when you send young boys to war. If it's humanly possible, if the prosthetics allow me, I'll go back to conflict zones. I wish I was in Libya at the moment, without a shadow of a doubt. Tom Stoddart, Sarajevo, 1992 I'm not really interested in military bang-bang pictures; I'm interested in documenting people living through war. Sniper Alley, where this was taken, paralysed Sarajevo. To get from one side to the other, the residents had to pass through this intersection and Serbian snipers would take shots at them. Bullets pinged past the entire time. Some people would sprint as fast as they could; others would brazenly walk, as if they were giving two fingers. Many were killed. Anyone who says they aren't frightened during war is either lying or a fool. It's about finding a way of dealing with the fear – you have to be very calm. You're not there to get your rocks off; you're there because you feel your pictures can make a difference. Sarajevo was the most dangerous place I have worked on a long-term basis. But I could leave. The occupants of Sarajevo couldn't. That was one of the strange things about covering it – it was so close to London. You could be back at Heathrow in a couple of hours. People would pass carrying skis, or off to the Caribbean, and you'd feel like screaming, "Why don't you understand?" You become a terrible dinner guest. Greg Marinovich, Soweto, 1990 I was deep in Soweto when I saw a man being attacked by ANC combatants. The month before, I'd seen a guy beaten to death – my first experience of real violence – and hadn't shaken the feeling of guilt that I had done nothing to stop it. "No pictures," someone yelled. I told them I'd stop shooting if they stopped killing him. They didn't. As the man was set on fire, he began to run. I was framing my next shot when a bare-chested man came into view and swung a machete into his blazing skull. I tried not to smell the burning flesh and shot a few more pictures, but I was losing it and aware that the crowd could turn on me at any time. The victim was moaning in a low, dreadful voice as I left. I got in my car and, once I turned the corner, began to scream. You're not just a journalist or a human being, you're a mixture of both, and to try to separate the two is complicated. I've often felt guilty about my pictures. I worked in South Africa for years and was shot three times. The fourth and final injury, in Afghanistan in 1999, wasn't the worst, but I decided enough was enough. I was looking to settle. Nineteen months later, I met my wife. Gary Knight, Iraq, April 2003 This was at the start of the invasion. We were at the Diyala Bridge, which had to be taken by the marines so they could get into Baghdad. They were the lead battalion, the ones who went on to pull down the statue of Saddam. The opposition were shelling us. It was terrifying – both the actual shelling, and the anticipation of it. It comes in waves so you can see it moving in your direction. One had exploded in the tank. If it had landed on top or a couple of feet over, I would have died. Your instinct is to bury yourself, but you can't. You're there to do a job. The point is to get the news out. If you keep moving, you can manage the fear. And my stress is nothing compared with civilians and soldiers. I remind myself of that all the time. I don't have to be there – they don't have the choice. My wife and children were very much on my mind because the danger was so extreme. You cannot separate the rest of your life and I've tried not to control how much I think about them. Sometimes they have been constantly in my head, sometimes I have not thought about them at all. Shaul Schwarz, Haiti, February 2004 Port au Prince was falling. It was riotous, with widespread looting. A group of us had gone to the port. The thugs with guns didn't want us there. We snapped from the waist, trying not to make it obvious. We decided to go over the wall. One thug offered me "protection". As we jumped the wall, I saw this boy, and was like, "This is what it's come to." It was my first digital assignment and I was amazed to be able to look at my shots. I did for a second; when I looked up, everyone had run off. It was just me and the thug. It was like a dog that smells fear. He began pushing and threatening me. Then I was surrounded. One of them hit me. I had a few dollar bills in my trousers, and put my hand there. They began tearing at me, fighting over the bills. I waited 30 seconds, started to walk away, then ran and scaled the fence. On the other side, I tried to breathe. I began shooting one guy a metre away. He screamed and pulled a shotgun. I saw the barrel, then he shot the man next to me – I had blood on me, brains. I was crying, shaking. I ran to the car horrified; I was a mess. I love Haiti, but every time I pass the port, I carry some of that fear. Eric Bouvet, Chechnya, May 1995 It was unbearable. Two crazy weeks and the most unbelievable story I ever did. I was with a Russian special commando. They were torturing, killing and raping. I saw them do it, and I couldn't stop them. Someone of a normal constitution can't accept that. I was working on the edge. This is the morning after a night that left four men dead and 10 wounded. It was heavy fighting, and I was very afraid. I discovered a dead Chechen four metres from me when I got up in the night. You see movies, you read books, you can imagine anything. But when you are in front of something, it's not like the movies. We started out as 60 and came back 30 – one in two people injured or killed. I was lucky. As soon as it was light, I took pictures. This is the first thing I saw. The guy with the bandage on his head has lost his friends. He has fought all night long. I don't feel pity, but at the same time they took me with them and did everything to protect me. Without them, I couldn't have done the story. I was the only witness. It's very complicated. Mads Nissen, Libya, February 2011  Mads Nissen: 'Suddenly this guy jumped on the the tank. I'm not that interested in pictures of tanks burning – I'm interested in people. I had wanted to capture the sense of release that everyone had, and this became the shot.' Photograph: Mads Nissen/Berlingske/Panos Pictures Mads Nissen/Berlingske/Panos Pic I got into Ajdabiya shortly after its fall. The rebels had just moved in and the locals were going crazy, shooting in the air. Bodies of pro-Gaddafi soldiers were lying around, beginning to stink as the sun got higher. The fire from the tank was incredibly strong and I was worried it might explode at any moment. Suddenly this guy jumped on to it. I'm not that interested in pictures of tanks burning – I'm interested in people. I had wanted to capture the sense of release that everyone had and suddenly this became the shot. I got as close as possible, within metres, and started shooting, counting to five in my head. Then I got out. I had seen corpses, torn apart, in the morgue and didn't want to end up like that. I took a chance – I had to; that was why I was there, to tell the story – but I made sure I wasn't too greedy. Adam Dean, Pakistan, December 2007 I was very much a novice when I took this. I'd just finished a master's in photojournalism and thought I'd go to Pakistan to cover the elections. An attempt had been made on Bhutto's life two months earlier, so there was already a certain degree of risk. I was about 15 metres away, photographing Bhutto, when there was a burst of gunfire followed by an explosion. I had a split-second decision to risk a secondary blast (as had happened in October) or start running with the crowd. I was panicking, trying to fight the urge to leave. I'd never seen a dead body before. It was almost like a test, to see if I had what I needed for this job. As I approached the aftermath of the bomb, I struggled to compose myself. I was terrified and sickened, but kept telling myself just to concentrate and get it done so I could leave. I knew I had to frame the pictures so they weren't too graphic. The epicentre of the explosion was a pile of maybe a dozen limbless, charred, mangled bodies in pools of blood. This was one of the times I was most in danger, but there have been times in Afghanistan where I have felt more scared. This was over in seconds, but a firefight can go on for hours. The real worry is IEDs, though – when you go on patrol, every step could be your last. I'm 33 and I'm not sure I'd want to put myself in such risky situations when I'm older and perhaps have other people to consider. John D McHugh, Afghanistan, May 2007 This is the last picture I took before I got shot. I'd been embedded with US troops in Nuristan for five weeks when we went to help a unit that had been ambushed nearby. There were bodies on the road, dead and dying. Taliban started shooting down on us from the mountains. I jumped behind a rock. I could hear bullets hitting it, and thought, "Oh fuck, oh fuck." We ran behind a Humvee, but now we were being fired on from both sides. By that point I'd accepted that I was going to get shot. There were so many bullets in the air, it sounded like a swarm of bees. They had us pinned down and a sniper was picking people off one by one. The bullet went through my ribs and out of my lower back. It felt as if I'd been punched. I fell to my knees, but managed to get behind another rock. The entry wound was the size of a penny; the exit bigger than the palm of my hand. The pain was overwhelming. I was convinced I was going to die and felt angry with myself. Then I started worrying that I might live but end up paralysed. Maybe I was better off dead? My mind refocused and I thought, "No, fuck that!" It was 25 minutes before anybody could get to me. My cameras were on the ground, and as they grabbed me I had to lean down and pick them up. When we got to the local base, a medic said, "Hell, I can see right through you." As soon as I knew that I'd recover, I told my girlfriend I was going to go back out. The work I do is important and also, if I hadn't, it would mean I'd never really understood the risks in the first place. I love my job but getting shot made me think about life beyond work. I proposed to my girlfriend two months later, and we had a baby last year. Marco di Lauro, Iraq, November 2004 This photograph was the most dangerous moment in my career. I was with two marines trying to get into this house. The first marine knocked down the door and the guy that you see in the image threw a grenade at him – the dust is from the explosion. Being behind the wall at the side of the front door saved me.The second marine entered the room and shot the Iraqi dead. I was the third person in the room and I took this picture. I started when I was 28. I'm 40 now, and a lot has changed in the risks I'm prepared to take. When you're younger, you're immortal. Three days into my first assignment, I was photographing between two lines of people shooting at each other in Kosovo. I'm more scared now, more aware of the risks. I've lost a lot of friends and colleagues – two of them very recently. I'll keep doing the job I do but I'll be more careful. John Stanmeyer, East Timor, August 1999 There were numerous firefights going on between the pro-Timorese Aitarak and the Indonesian militia, so I just ran. A bullet went right by my ear, moving my hair. It was fate that my head was tilted to the right, otherwise I wouldn't be here today. Within minutes of nearly being killed, I came across pro-East Timorese independence supporter Joaquim Bernardino Guterres. The military turned their guns on him, and as he started to run they grabbed him and kicked him. Moments later he was lying in a 20ft stream of blood. The military were very unhappy with the pictures afterwards. I don't think about the risk to myself, as I probably should. While I was out in Afghanistan, my wife had a miscarriage and she equated it to my being away. That was pretty dreadful, but she's a writer and understands why I do this. We've been to Sudan together, we've been ambushed, we've been in lots of nutty situations. Ashley Gilbertson, Iraq, 2004 It was one of the most intense experiences I've ever had. I was with a lead unit of marines, and we received a triple ambush from the insurgents. I'd just run across a street with 40 marines to take shelter in an Islamic cultural centre, with bullets whizzing past my face. I thought, if I'm going to die right now, I might as well be working. I was in so much shock. It was a wake-up call to how violent it was going to be. The guy in the photo is shouting, "Don't take my fucking picture!" Sometimes, you look at images of war, and they're like a Hollywood producer's vision of what war is supposed to look like. There are very few pictures where you get a feel for how fucking awful it is, how desperate and urgent. I like that it's not a clean picture, that it's not well composed and you can't see everything that's happening. That's part of it. It's so messy. It's the closest I've come to capturing the chaos of combat. Ron Haviv, Bosnia, 1992 These are the Serbian warlord Arkan's men. They've just executed these Muslim civilians – a butcher, his wife and sister-in-law; the start of what became known as ethnic cleansing. I had taken a photograph of Arkan with a baby tiger, which he'd liked, and he'd agreed for me to travel with his troops to photograph his "mission". The soliders were yelling at me not to shoot, but I'd promised myself I'd come out of this with an image to prove what was happening. I was shaking when I took this shot. None of them was looking at me so I lifted my camera, just trying to get them in frame. When I put it down, they looked over. They didn't realise I'd taken photos. Later, Arkan caught me photographing another execution and said he'd process my film and keep the ones he didn't like. I'd hidden the film from earlier in the day in my pocket and figured that if I fought hard enough for the film in my camera, he wouldn't search me. When the pictures were published not long after, Arkan said in an interview, "I look forward to the day I can drink his blood." He put me on a death list, and I spent the next eight years trying to avoid him. Eventually, these images were used to indict him at The Hague. Julie Jacobson, Afghanistan, August 2009 We were hiding from Taliban gunfire, when there was this explosion. Afterwards, I saw [Lance Corporal Joshua M] Bernard – one of his legs was blown off and the other was barely there. He'd suffered a direct hit from an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade]. The media ground rule was that you couldn't photograph a military casualty in a way that they could be identified, but I could see Bernard's hand reach out to his weapon, his face turned to me. So I shot nine frames over two and a half minutes. Making that decision was a public act. I got a lot of flak. Bernard later died, and people said that I didn't give him dignity, that I should have helped him. But I couldn't help him. For me to turn my back, that's disrespectful. Ami Vitale, Gaza, October 2000 I was photographing a funeral, and having spent most of the day with the women, I went to see the body being taken in. A man in the procession started screaming, "CIA agent" and pointing at me. I was surrounded by hundreds of angry men, screaming in my face, grabbing me. I was terrified, and thought, "This is it. I am going to die." Suddenly I understood a mob. There's no thinking, just passion.

A woman I'd spent the day with managed to pull me away. When I got home, I sat and cried and cried – she had saved my life. I stayed on in Palestine, but was much more cautious after that; have been ever since. That moment changed my perspective. No picture is worth it. 原文:https://www.theguardian.com/media/2011/jun/18/war-photographers-special-report/amp |

|||||||

- 主頁

- 有關流白之間

- 課程及活動

-

過往項目

-

課程/工作坊

>

- Thomas Richards【Threads of Creation—Hong Kong】歌謠詠唱及劇場創作大師班

- 桑田貴志「風姿花傳」能劇大師班

- 馬汶萱「舞蹈創作中的劇場構作」工作坊

- Thomas Richards【歌謠的潛力—香港】大師班

- 吳文翠「太極導引」 實地線上工作坊 >

- 黃子翎「I'm 菜鳥」慢鼓初階工作坊

- 張藝生 一心擊鼓基礎工作坊 (2022年9月)

- 張藝生 一心擊鼓基礎工作坊 (2022年8月)

- 「龍」表演探索計劃 第一回 工作坊

- Wendell Beavers「Viewpoints」表演訓練實地線上課程

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演訓練課程第二階段:獨白與文本

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(專業舞者特別場Ļ

- 彭思硯「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(Introductory 2021 Summer)

- 張藝生 一心擊鼓基礎工作坊 (2021年7月)

- 跨界別Battle工作坊

- 黃家駒、彭思硯「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(Introductory 2020 Fall)

- 江駿傑 戲曲的當代身體性-訓練及實驗分享工作坊

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(專業舞者特別場Ļ

- 皮部針療法課程(抗疫優惠版))

- 第四屆「舞台表演者-中醫基礎知識及推拿課程」

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(專業舞者特別場)

- Stephen Wangh's「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(APA特別場)

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(Introductory 2019 Fall)

- 黃子翎 擊鼓練功房

- 黃家駒「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(Introductory 2019 Summer)

- 黃子翎 擊鼓進階班

- 黃子翎「I'm 菜鳥」慢鼓初階工作坊

- Sunhee Kim「獨腳片段的創作」:身心合一(Psychophysical Approach)表演體系訓練及實踐課程

- 陳偉誠「成為一個完整的人——葛羅托斯基體系工作坊」

- Stephen Wangh's「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演訓練課程第三階段:角色的塑造

- 伍宇烈肢體及跨媒介創作工作坊 3.0

- 吳文翠「溯。源。覺。行 2」 工作坊

- 林晏甄「身體譜」 探索核心空間工作坊

- 黃子翎「聽見勇氣——真誠的面對自己」擊鼓練功房

- Stephen Wangh's「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演訓練課程第二階段:文本與獨白

- Stephen Wangh's「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 入門訓練課程(Introductory 2018 Spring)

- 第三屆「舞台表演者-中醫基礎知識及推拿課程」

- 黃子翎「聽見耕耘——把自己種回來」擊鼓練功房

- 伍宇烈肢體及跨媒介創作工作坊

- Sunhee Kim「文本的力量」:身心合一(Psychophysical Approach)表演體系訓練及實踐課程

- 「綿軟舞步,輕鬆行路」自然步行工作坊

- Bambang Besur Suryono「身體朝聖」印尼爪哇形體聲音及 宮廷舞面具劇 訓練課程

- Stephen Wangh's「心之飛人」葛羅托斯基體系表演 訓練課程

- 吳文翠「溯。源。覺。行」 工作坊

- 黃子翎「聽見歸零-扎根的力量」慢鼓工作坊

- 梁遠光 太極對練及腰功鍛鍊日營

- 吳文翠 太極導引與葛羅托斯基「神祕劇」(Mystery play) 工作坊連展演

- 黃子翎「聽見流白」慢鼓工作坊-聆聽自己的第一個鼓聲

- 梁遠光 太極對練入門課程

- Sunhee Kim「身心合一」(Psychophysical Approach)表演訓練密集課程

- 皮部針療法課程

- 第二屆「舞台表演者-中醫基礎知識及推拿課程」

- 第一屆「舞台表演者-中醫基礎知識及推拿課程」

-

主辦演出/特備活動

>

- Theatre No Theatre《The Inanna Project》亞洲首「演」

- Kei Franklin《Just A Little Too Much》預覽版

- 澳門優秀劇本香港讀劇活動2023

- 沈旭暉Simon Patreon x 流白之間 巴勒斯坦劇本《The Revolution's Promise革命的承諾 》 網上讀劇演出

- 沈旭暉Simon Patreon x 流白之間 伊朗劇本《A Moment of Silence片刻寂靜》網上讀劇演出

- Theatre No Theatre【Presentation of Songs】演出暨交流對談會

- 沈旭暉Simon Patreon x 流白之間《Bad Roads》網上讀劇網上籌款讀劇義演

- 沈旭暉Simon Patreon x 流白之間《侮辱。白(俄)羅斯 2.0》網上廣東話讀劇

- 《侮辱。白(俄)羅斯》Insulted. Belarus(sia)國語讀劇

- 《侮辱。白(俄)羅斯》Insulted. Belarus(sia)廣東話讀劇

- 《侮辱。白(俄)羅斯》Insulted. Belarus(sia)英文讀劇

- 《香港人.藝術.在彼邦.於當下》 線上交流會

- Dance me til the end of... 沙龍小晚會

- 臺灣・香港演作交流計劃《猶在》

- Stephen Wangh x 陳偉誠對談 —— 葛羅托夫斯基逝世20周年 · 葛氏精神如何在21世紀延續

- 台灣小劇場學校演作交流計劃《謹守:眼耳鼻舌身》作品聯演

- 共學講堂 - 台灣小劇場的「精神」素描

- 「鼓子回家,擁抱自己的足跡」分享會

- 伍宇烈 x 潘璧雲 x Mike Orange 分享對談: 舞蹈、文字、音樂的跨媒介碰撞

- 「修行與表演」分享座談

- Besur x Sunhee x 梁曉端 x 吳紹熙分享對談: 跨文化身體訓練在當今劇場的實踐

- 郭勁紅 x 林俊浩分享對談:「從國際經驗看香港」-關於跨界別表演

- 無垢舞蹈劇場紀錄電影《行者》播映及討論會

- 吳文翠作品《蛇,我寂寞》

- 【竹の響】 古典尺八分享會

- 當代歐洲劇場面面觀

- 光影之間 >

- 協辦劇場

-

2015-16年度 駐場藝術家及策展計劃

>

-

課程/工作坊

>

-

文章資源

- Thomas Richards專訪:知識和技術的傳遞(文:Steve Capra、翻譯:黃家駒)

- 藝乘的身語意修行(翻譯:黃家駒)

- Thomas Richards與Jerzy Grotowski的相遇(翻譯:黃家駒)

- 葛羅托斯基「個人品牌」的形成、傳播與接受(文:黃海)

- 一直受自我懷疑所折磨的史坦尼斯拉夫斯基(文:Simon Callow)

- Stage-fright的樂趣、Failure的成功(文:Stephen Wangh、翻譯:黃家駒)

- 以動禪太極導引作為展演前暖身:創造沉靜能量態的身心空間(文:吳文

- 布萊希特《中國戲劇表演藝術中的間離效果》

- 表演作為一種獻祭 - 給香港演藝學院戲劇學院三年級學生的演講(講者:Step

- Sunhee Kim's「修行與表演」分享講座記錄

- 梅蘭芳《紀念斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基》

- 《溯源覺行2》展演後座談會紀錄

- 表演的次第(文:張佳棻)

- Stephen Wangh北藝大《直視不完美:如何在危險的世界裡搞藝術?》演講講稿

- 屠龍:究竟刀來自何方?(文:何應豐)

- 葛羅托斯基致研討班畢業生的演說(校譯:黃家駒)

- 溯什麼的源,覺什麼的行?(文:黃家駒)

- 表演的政治性(文:Stephen Wangh、翻譯:黃家駒)

- Stephen Wangh x 陳偉誠對談 《葛氏精神如何在20世紀延續》文字全記錄

- 文化連結

RSS 訂閱

RSS 訂閱